Before he was Sir Andrew Murray OBE, world number one, three-time Grand Slam champion, one of the nation’s greatest-ever athletes… he was, to one woman at least, something altogether less celebratory.

In 2006, the football World Cup was taking place at the same time as Wimbledon. A 19-year-old Murray, himself once a promising youth footballer, joked in an interview that he would support “whoever England were playing against”.

It went down like a lead balloon. He was abused in the comments of a blog he wrote on his website and even his wristbands, decorated with the Scottish saltire, attracted scrutiny.

Murray had become a lightning rod, attracting ire in an edgy Anglo-Scottish atmosphere. The previous month, the then Scottish First Minister had been criticised for saying he would not be supporting England.

But the reaction to Murray’s joke was on a far larger scale.

In the aftermath, Murray, playing only his second Wimbledon, walked past a spectator on the way to his match. He overheard her telling a friend, in expletive-laden and anti-Scottish language, that she had just spotted him.

“I was like, What? I was 19. This is my home tournament. Why is this happening?” Murray remembered in a 2017 interview., external

“I was still a kid and I was getting things sent to my locker saying things like: ‘I hope you lose every tennis match for the rest of your life.'”

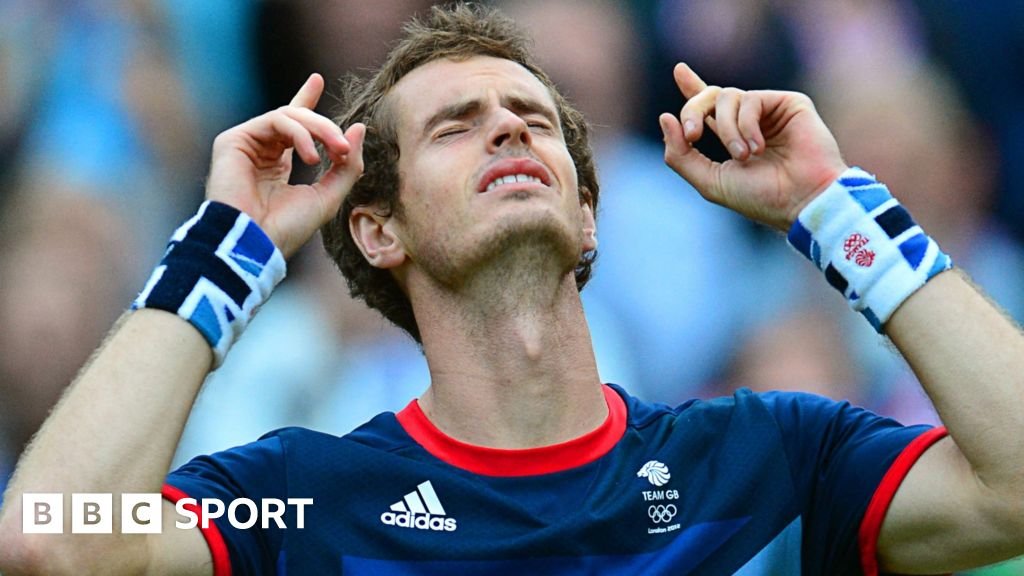

By the time 2012 rolled around, Murray had already broken new ground.

He had reached the US Open final in 2008, becoming the first British man to make a major final since Greg Rusedski in New York 11 years earlier.

Two further Slam final appearances followed – the Australian Open in 2010 and 2011 – but Britain was still searching for a first male major singles champion since Fred Perry in 1936.

But the ambivalence of some of the general public remained.

As the Twitter joke went, Murray was British when he won and Scottish when he lost.

It sometimes seemed there was something inordinate about Murray – his outspokenness was loved to a certain point, his on-court anger amusing when he was winning but derided when he was losing.

At this point, Murray was a nascent member of the Big Four. Roger Federer was transcendent, described as a ‘god’, especially at Wimbledon. Rafael Nadal had the grit, the determination, the never-say-die attitude.

Novak Djokovic, another relative newcomer trying to upset their duopoly, defied belief, limbs bending every which way, equipped with an endurance level and mental strength few can match.

But Murray? Murray was the most human. A man who sometimes looked as if he actively hated the sport of tennis. No-one could ever accuse Murray of hiding his emotions. And that rubbed up some the wrong way.

He was accused of being whingey, of being anti-English, of being boring, when really he was doing what we all do – getting frustrated about the job and attempting to have a laugh along with it.

“I think it’s very difficult for any young player who is thrust into the spotlight to get to grips or feel comfortable with facing and understanding the media,” said his mum Judy, speaking on Andy Murray: Will to Win, a recent BBC Sport documentary.

“One of the things in tennis is that players have to face the media after every match whether they win or lose. Of course, it’s a lot easier to face the media when you’re winning.

“As an 18-year-old he’d had a little bit of media training but nothing really prepares you for suddenly being in front of a room of about 300 people.

“I think his reaction to anything is to be truthful and say what you’re thinking. In years to come, you will become much more practised.”

Source link