Our sun is far from the flawless orb of light we see in the sky. Spacecraft observations have long shown that, up close, the “surface” of our star rumbles with powerful eddies and is dotted with fiery sunspots that occasionally burp superheated material into space — a phenomenon that occurs even more frequently during phases of increased turbulence on our star, like the one we’re experiencing now.

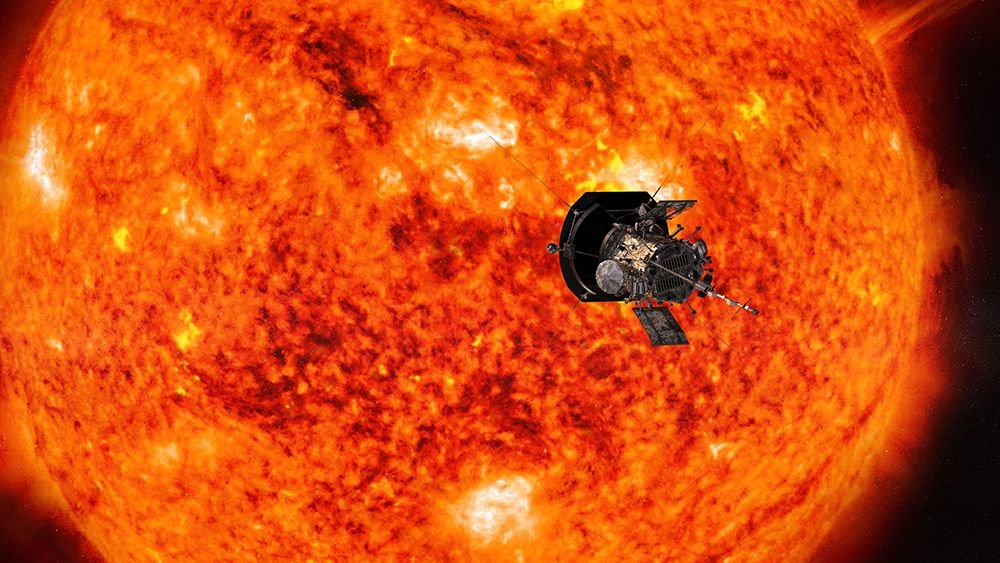

Scientists are hoping NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will get a unique taste of the sun’s wrath on Christmas Eve, when it will swoop within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the sun’s surface — the closest yet a human-made object has ever gotten to our star. At this record distance, the probe is already expected to cut through plumes of plasma still rooted to the sun, akin to a surfer diving under a crashing wave.

The sun reached its most turbulent phase in its 11-year cycle just two months ago, so scientists are hoping it will unleash at least one solar flare that serendipitously passes through the same pocket of space as the Parker Solar Probe. Far from damaging the spacecraft, this would allow the probe to gather rare data about how the sun’s charged particles are accelerated to near-light speeds and dissect the dynamics of space weather — insights that would be valuable not only for understanding our sun but also for studying stars elsewhere in the universe, scientists say.

Since Parker Solar Probe launched in 2018 on a historic and audacious mission to decode some of the sun’s deepest secrets, it watched our star transition from a calm, so-called solar minimum to its current stormy state, marked by back-to-back solar flares this summer that sparked the strongest auroras in 500 years.

“The sun is doing different things that it did when we first launched,” Nicholeen Viall, who is a co-investigator for the WISPR instrument onboard Parker Solar Probe, told reporters earlier this month at the Annual Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU). “That is really cool because it is making different types of solar winds and solar storms.”

Viall and the rest of the mission team are confident the spacecraft will withstand solar flares, largely because the probe easily survived its strongest flare so far in September 2022, which occurred on the back side of the sun and out of sight of mission control.

“The Parker Solar Probe is designed for that,” Nour Raouafi, who is the project scientist for the mission, told Space.com in a recent interview. The spacecraft “dealt with it beautifully,” he added, about the 2022 solar flare. Flying in the wake of that flare, Parker’s data confirmed the decades-old hypothesis that a coronal mass ejection acts like a vacuum cleaner, clearing dust out of its path and leaving behind a near-perfect vacuum.

Any flare barreling toward Parker Solar Probe will be seen not by the spacecraft itself, which will be incommunicado with mission control, but by other sun-observing spacecraft like the European Solar Orbiter. Scientists will know how Parker Solar Probe dealt with any such events when the spacecraft gets back in touch with mission control through a critical beacon tone on Dec. 27, followed by images as well as science data in the New Year.

The sun’s turbulence is now such that the four science instruments onboard Parker may soon even study powerful solar flares occurring on top of each other, providing scientists with up-close data about the chaotic workings of our star.

“We are preparing to make history,” Raouafi said at the AGU meeting. “Parker Solar Probe is opening our eyes to a new reality about our star.”

Source link