My father struggled to talk with me. But he found the words when it mattered most

This First Person column is the experience of Siobhan Kellar, who lives in Calgary. For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

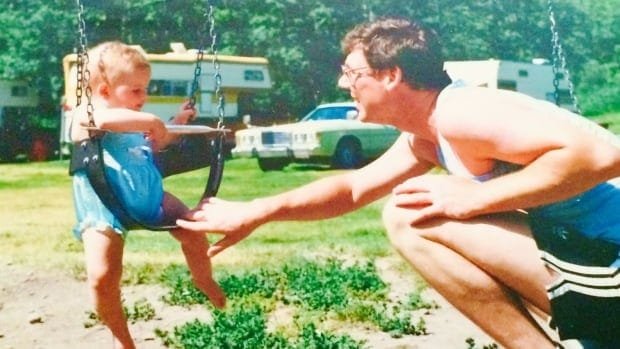

My father used to sing to me as a baby. As a preschooler, I’d insist he change the lyrics of “Yellow Submarine” to all the colours I could think of as he held my hand on our way to buy Coca-Cola on Saturday mornings.

I was delighted by his songs, and then, as a teenager, I wasn’t. My cheeks would burn and I’d steep in shame when he’d hum along to the radio, always out-of-key, as he shuttled my friends and me to soccer practice.

My dad and I had a difficult relationship.

I think that he was afraid of big emotions and overwhelmed by them. I don’t really know why. He grew up in England and moved to Canada by himself during his late teens.

As for me, I had undiagnosed ADHD as a child and a sleeping disorder that made me restless and irritable. I reacted to conflict by retreating and searching for a space I could control.

When we tried to communicate, it seemed we’d trip on hidden triggers. Music was the only neutral territory. He introduced me to Oasis, New Order, The Kinks and LCD Soundsystem. Some of our most intense conversations were indirectly transmitted through the tinny speakers of his maroon Mazda.

“Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 64?” and “We can work it out” from the Beatles are still etched in my heart. I understood that he wasn’t just sharing music. He was saying he would be there for me and love me no matter what.

That was enough until my first year of university. That’s when my dad moved out of our family home and my parents initiated their divorce. I should have seen it coming; they’d been fighting since I was little but it still hit hard.

Unable to do anything about my parents’ problems but feeling the pain of their separation, I took to controlling my body instead. What began as trying to eat better rapidly morphed into bulimia. A year later, I was seen at the eating disorder intake in Calgary. My heart was weak and I required hospitalization.

My dad picked up toiletries, slippers and pyjamas from Walmart and drove me to the hospital. I pretended not to see him cry when he hurried out the door.

Days turned to weeks and I had to take a leave from university. The loneliness hit me on Saturday nights when I sat in my hospital bed, miserably commenting “Congratulations!” on friend’s Facebook timelines as they celebrated the end of term.

With my headphones on and only a curtain for privacy between myself and the other clients, I’d listen to Bon Iver on a loop and let the tears come. I wanted to quit the program, which could have been a death sentence.

My dad must have recognized how the stakes had shifted. During visiting hours one unseasonably warm spring day, he snuck me outside for a few minutes of sunshine. We exited the cafeteria doors to the loading dock.

This time he didn’t try to use music. He asked me to hold his tea, then took 10 steps. He turned to face me. His shoulders and jaw looked tense but he pushed through.

“This is how far you’ve come, Shev.”

He took two steps back toward me.

“This is just a tiny stop on your journey. It’s not where it ends.”

I shifted my weight to the other foot and looked away. I was 21; talking to my dad like this felt raw.

“You’ll look back at this and instead of worrying about falling behind at university and not being who or where or what you want to be, you won’t even notice this blip, because you’ll be —” and he paused, and took 30 steps further away from me “—here,” he called, shouting now to be heard.

“And you have all that way to go after,” he said, gesturing to the expanse of grass that began where the lot ended.

He walked back to me and kissed my forehead before taking his tea back. I tried not to flinch.

Later he told me that when I recovered (when, not if), he and I could get matching tattoos for the “Ed” — my name for the eating disorder. I stifled my laughter, imagining him with a tattoo on his wrist that could be misconstrued as erectile dysfunction.

In the end, I was one of the lucky ones. After several inpatient stays and months of outpatient programs, I did eventually beat the eating disorder. It’s not like my dad cured me, but he helped with my grief; he helped me gain perspective.

I moved on from that — finished university, got a job as a teacher and started a family of my own. Now he lets my daughters pick the colours when he sings “Yellow Submarine.” I still remember his words when disappointments come, and when I struggle to articulate my own feelings, I turn up the music.

Maybe years from now, my daughters will catch a bar of a Taylor Swift song. They’ll hear “People throw rocks at things that shine” and remember it as a message of love.

Telling your story

This First Person piece came from a writing workshop run in partnership with the Calgary Public Library at the Crowfoot branch. Read more about CBC Calgary’s workshops at cbc.ca/tellingyourstory.

More personal stories from CBC writing workshops:

Source link