The Two Paul Rudolphs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rudolph with the building he designed for the Yale School of Architecture.

Photo: Yale University News Bureau/© Yale University.

The architect Paul Rudolph was a superstar when he left an academic career and opened a New York studio in 1965, a symbol of all that American inventiveness, might, and optimism could achieve. Four years later, he had become a middle-aged living memory, the phenomenally talented emblem of his cohort’s arrogance. He rejected his predecessors’ gossamer boxes and redefined modern architecture as an art of texture, shadow, complexity, and weight. He believed the car was the seed from which new cities grew and saw dense city blocks as history’s crumbs to be swept clean. Rudolph aspired to leave buildings that would endure for millennia, but within a couple of decades after his death in 1997, they began vanishing in the regular rhythm of the wrecking ball.

Rudolph has never been the subject of a major retrospective, and the Metropolitan Museum hasn’t mounted a modern-architecture show in 50 years. The Met curator Abraham Thomas fills in both those crevasses with “Paul Rudolph: Materialized Space,” a compact but revelatory exhibition that presents the architect in all his irreducible thorniness as virtuoso and ravager. You can come away loathing the guy or awed by him. I did both.

Starting in 1957, he spent eight years at Yale, and in between teaching and terrifying students, he designed a new facility for doing both. The Art and Architecture Building, his most famous project, is a concrete confrontation: brawny, rough-hided, complex with floating layers anchored to the earth by massive vertical piers. It declared that Rudolph’s profession, like rocketry, highways, and nuclear fission, was the means to make America new again. The only history that mattered was antiquity, like the Roman aqueducts that inspired another New Haven calling card, the dramatically arcaded Temple Street Garage. The 20th century would leave its own imperial monuments.

Inside the Architecture Building, power and pedagogy merged. Light fell into the atrium from above in a cathedral-like shower, and the first, second, and third-year students were arranged around it on upper floors with the fourth-years in the well, where they could be observed and envied. “It was totally hierarchical; you worked your way to the center stage,” observed Robert A.M. Stern, who studied under Rudolph and later followed in his footsteps as the architecture school’s dean. That approach mirrored the master’s teaching style, which could be cultish in its mixture of worship and oppressiveness. “He would brutalize people,” one of his disciples, Stanley Tigerman, recalled. “Paul was a miserable, mean bastard [but also] simply the best teacher I ever had by far … He was fabulous, he was a killer. Yale, but Paul Rudolph, specifically, invented me out of whole cloth. He fabricated me.” Soon the ’50s spirit of discipline collided with the next generation’s ethos of rebellion. When a fire broke out in the Yale building in 1969, the immediate (though false) assumption was that student-inmates had tried to burn the place down.

His Yale Art and Architecture Building displays a complex interplay of windows and levels and shafts of light.

Photo: G. E. Kidder Smith/© Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Born in 1918, Rudolph belonged to a generation of Americans whose concept of urbanism was formed by their nation’s demonstrated power to destroy and construct on a similarly vast scale. Stationed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War II, he witnessed the military-industrial complex turn out giant technically advanced warships. Later, he found that the same thick concrete armatures that supplied all-but-indestructible bunkers could also be deployed for an equally sturdy peacetime architecture. The factories that had cranked out weapons could be repurposed to produce housing en masse. He imagined a tower made of stacked mobile homes, anticipating much later attempts to compose apartment buildings out of shipping containers or piled prefab modules.

The Met’s exhibition amazes in two contradictory ways: as a reappreciation of Rudolph’s artistry and as an assessment of his impact on the American city. The first was phenomenal, the second disastrous. A superb draftsman, he used drawing to clarify the drama of his ideas, to animate not-yet-extant spaces with the play of shadow and surface. Some remind me of Piranesi’s imaginary prisons with their multilevel interiors diagonally slashed by staircases and shafts of sunlight, their ambiguous atmosphere quivering with both horror and exhilaration. Rudolph translated those graphic effects into concrete, which, like paper, he could inscribe with his high-precision lines. The critic Reyner Banham wrote that the Yale building “is one of the very few buildings I know which, when photographed, was exactly like a drawing, with all the shading on the outside coming out as if it were ruled with a very soft pencil.”

But Rudolph thought in three dimensions, not just two, and he conjured spaces bristling with detail and complexity. During the period of his greatest glory, he designed the headquarters for Burroughs Wellcome pharmaceutical company in Durham, North Carolina, conceiving it to startle and to last. It achieved the first but not the second. The A-shaped structure, a hive of polygonal pods supported by V-shaped steel columns, created angled walls and exciting spaces, so that simply walking from a lab to lunch added up to a ceremonial procession. A National Parks Service report, part of a survey of historically significant buildings, drily captured its oppressive form of freedom. “While spatially liberating and architecturally provocative, the distinctive structural system also uncomfortably restricted workers’ movements and necessitated custom-designed furniture to fit the unusual interior volumes and structural protrusions.” The upshot was that, after a protracted valedictory, the Burroughs Wellcome Headquarters was finally demolished in 2021.

The sci-fi Burroughs Wellcome Headquarters in North Carolina, completed in 1972 and demolished in 2021.

Photo: Joseph W. Molitor/Colombia University

Wes Anderson captured some of Rudolph’s spatial excesses in the movie The Royal Tenenbaums, in which the character played by Ben Stiller lives in the multilevel Beekman Place penthouse that Rudolph designed for himself. Stiller stages a fire drill, hustling his kids through an interior teeming with stairs, mezzanines, and disorienting changes of direction. (The escape takes too long, he concludes: “We’re all dead. Burnt to a crisp.”)

Rudolph’s landmark house at 23 Beekman Place.

Photo: Ed Chappell/Courtesy Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture

Even as it provokes artistic admiration, the Met show helps explain how a corps of dedicated creators and planners could get away with pulverizing large swaths of American cities and urban society. Rudolph belonged to a cohort of powerful white men with bristle-top haircuts and narrow ties who knew in their bones how Americans should live and work and how they should get from one activity to the other. (By car.) His architectural aspirations jibed with politicians’ ideas about cities, and they supercharged each other’s hubris. He became a front man for urban renewal — a professional visionary who gave planners the aesthetic cover they needed. Sitting at a drafting table, armed with his mighty pencil and backed by the authority and purse of the federal government, Rudolph could wipe away entire neighborhoods, reshape cities, and erect monuments. He planned the town of Stafford Harbor, near Washington, D.C., and reimagined the Buffalo waterfront. When Boston bulldozed several neighborhoods to make way for its brutalist Government Center, he joined the project just in time to supersize it.

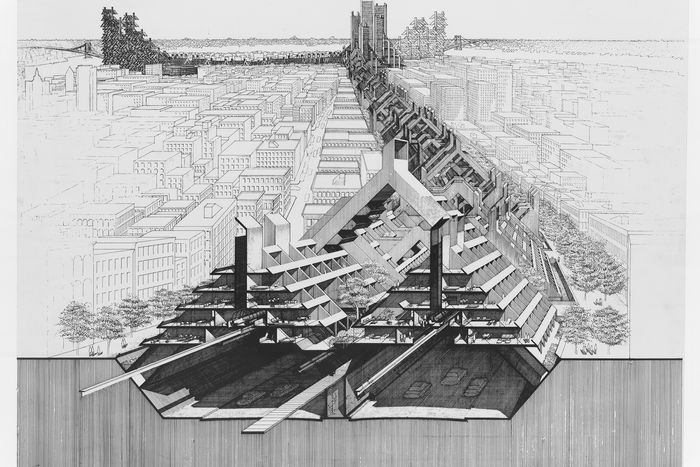

His belief in a future shaped by cars culminated in a fantastical, horrifying proposal for a Lower Manhattan Expressway. Robert Moses had already come to grief over a real-life plan to drive a multilane elevated highway through Soho. At the behest of the Ford Foundation, Rudolph out-Mosesed Moses, enfolding the traffic lanes in a two-mile-long high-rise complex, with cliffs of apartments flanking the road, that would have obliterated much of downtown. Fortunately, by the time he came up with this totalitarian fever dream, he had lost his clout. Sidelined by a country that had enough of technocratic hubris, he looked to Southeast Asia, where nations like Singapore and Indonesia were just starting to cultivate their own architectural grandiosity. In the 1980s, he designed the Colonnade in Singapore, expressing his early fantasies of stacked prefabricated modules that appeared to be suspended from slender, cablelike columns. Technically, though, it was a cheat, built using traditional construction methods with nothing factory-made about it.

Rudolph’s ambitious, monstrous plan for an expressway lined with apartments crossing lower Manhattan.

Photo: Prints and Photographs Division/Library of Congress

“Materialized Space” left me wondering how to separate the two Rudolphs, or whether his talents were inextricably tied to his time. The show is so focused on the auteur that it gives short shrift to his context or legacy. Rudolph didn’t spring fully formed from his own brow, and he was far from alone in his desire to assemble modules like pieces in modeling kits. It would have been nice to juxtapose his Stafford Harbor Plan with Peter Cook’s plan for a Plug-In City, the Japanese Metabolists’ Nagakin Capsule Tower, Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, or Branko Znidarec’s Hotel Adriatic on the Yugoslav Coast. You can still see that influence in the high-end architecture of today. A 1972 Life profile included a photograph of him erecting an intricate skyscraper out of Lego blocks. A generation later, Bjarke Ingels erected his own miniature megastructure out of LEGO blocks at the Storefront for Art and Culture and Architecture — a prelude to his own design for the LEGO Museum in Denmark. And while the era of urban renewal has (mostly) passed in this country, China has spent 30 years ginning up new cities so fast it’s started tearing portions of them down before they are even done, and Saudi Arabia has recruited a clutch of high-caliber architects to design a 100-mile-long linear city in the desert that, though carless, oddly resembles a megamagnified version of the LoMEx plan. Even as original Rudolphs keep falling — the Orange County Government Center in Goshen, the Shoreline Apartments in Buffalo, and most recently the Sanderling Beach Club in Sarasota, destroyed days ago by Hurricane Helene — his immodest spirit marches on.

The Shoreline Houses in Buffalo, now demolished.

Photo: G. E. Kidder Smith/© Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Source link