A new study published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry has calculated that millions of Americans are dealing with mental disorders attributable to childhood lead exposure—through exhaust from cars fueled with leaded gasoline.

Researchers found that those who were born between 1966 and 1986—Generation X— were the most lead-exposed, as they were children during the peak of leaded-gasoline’s usage. They also experienced the largest increase in mental illness symptoms, according to the study.

The study, from Aaron Reuben, a postdoctoral scholar in neuropsychology at Duke University, and colleagues Michael McFarland and Mathew Hauer at Florida State University, states that more than half of the current U.S. population was exposed to “neurotoxic levels” of lead via its use in gasoline.

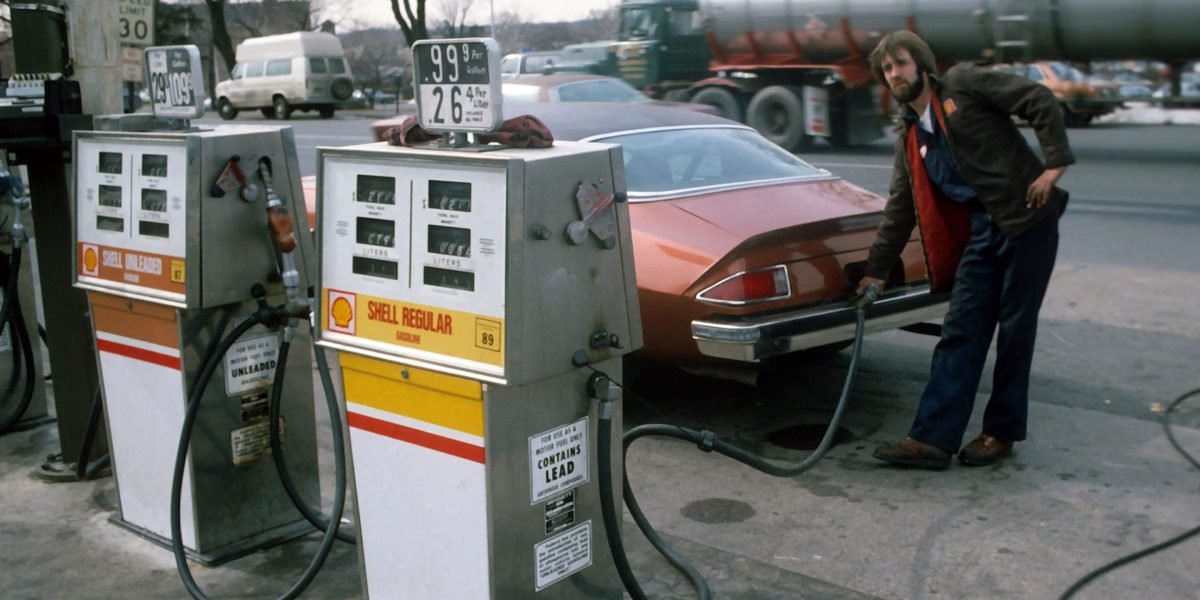

Lead was first added to gasoline in 1927 to keep car engines healthy; its use was gradually taken off the market starting in the 1970s due to both health and environmental concerns, and phased out completely in 1996.

To find out what kind of impact the exposure to lead-containing fumes had on mental health, researchers combined blood-lead level data from publicly available National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) with historic leaded-gasoline data to estimate childhood blood-lead levels from 1940 to 2015. They then calculated population elevations of mental health symptoms known to be associated with lead exposure by calculating “mental illness points.”

“This is the exact approach we have taken in the past to estimate lead’s harms for population cognitive ability and IQ,” McFarland told Science Daily, noting that the research team previously identified that lead lowered IQ points from the U.S. population over the past century by 824 million.

Their latest research estimates that 151 million cases of psychiatric disorders—including depression, anxiety, and hyperactivity— from the past 75 years can be traced to childhood lead exposure.

“We saw very significant shifts in mental health across generations of Americans,” Hauer told Science Daily. “Meaning many more people experienced psychiatric problems than would have if we had never added lead to gasoline.”

The researchers point out, however, that this study does not prove causation. They also note that it is only based on exposure to leaded gasoline, not factoring in other lead exposures from lead pipes, contaminated food and soil, or airborne dust from lead-emitting manufacturing, waste incineration, and lead processing operations.

How does lead affect the brain?

Lead exposure is most dangerous to children, and can be particularly disruptive to brain development in early life, researchers explained in the study. They noted that childhood lead exposure could result in decreased cognitive ability, fine motor skills, and emotional regulation capacity.

Numerous other studies have linked childhood lead exposure with mental disorders, the researchers wrote, including depression and anxiety, as well as personality changes that lead to neuroticism and lower impulse-control.

Even small amounts of lead can cause serious health problems, according to the Mayo Clinic. Children younger than 6 are especially vulnerable to the impacts of lead exposure, which can cause developmental delays, learning difficulties, and irritability, among other symptoms in children and newborns, from sluggishness and vomiting to hearing loss and seizures.

Babies exposed to lead before birth might be born prematurely, have lower birth weight, and have slowed growth—while adults can experience high blood pressure, joint and muscle pain, memory issues, headaches, mood disorders, reduced sperm count, and miscarriage or stillbirth as a result from lead poisoning.

“Humans are not adapted to be exposed to lead at the levels we have been exposed to over the past century,” Reuben told Science Daily. “We have very few effective measures for dealing with lead once it is in the body, and many of us have been exposed to levels 1,000 to 10,000 times more than what is natural.”

More on Gen X and health:

Source link