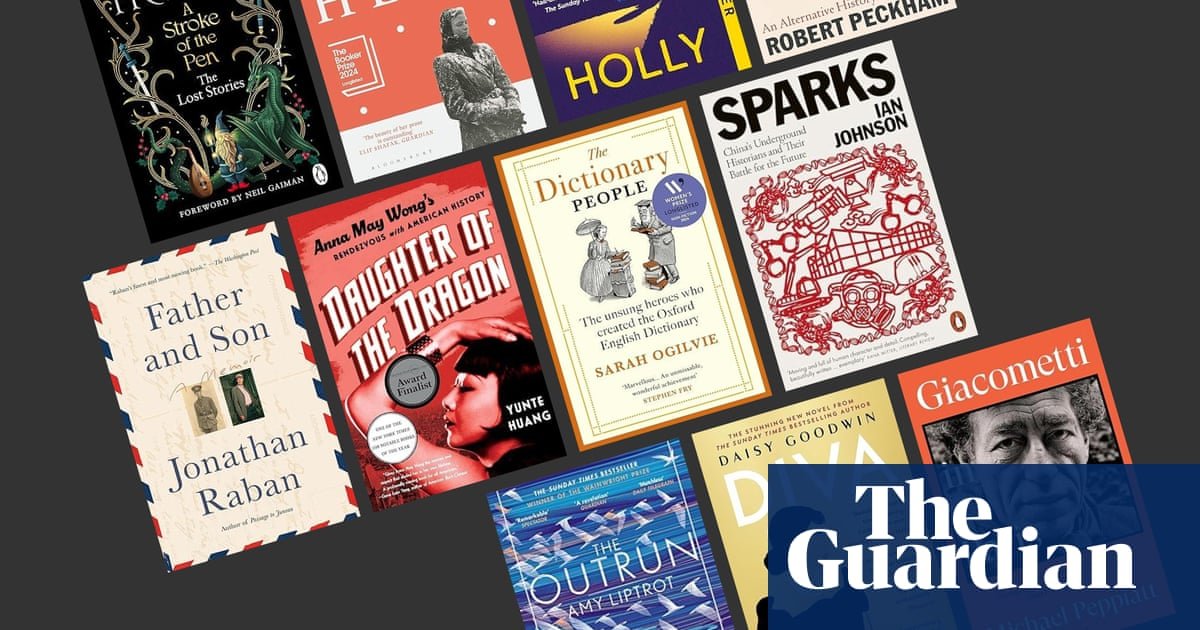

Short stories

A fantasist’s formative years

A Stroke of the Pen

Terry Pratchett

A Stroke of the Pen Terry Pratchett

A fantasist’s formative years

Fantasy can boast world-beating authors, but hungry readers have also had to suffer portentous tales of men with swords declaiming at one another across prose that takes half a page to say: “Yeah, but are you a werewolf, though?” – or, indeed: “Hello.” Pratchett was and remains the opposite of that. His plotlines are inventive, generous and offer fully formed female characters. Underlying his work is a characteristic sense that any thoughtful human might consider their species with weary fondness and cynical optimism. A Stroke of the Pen is a postmortem collection of short fiction, somewhat alarmingly described in the publicity as “unearthed”. It’s very early work, but Pratchett is already unmistakably Pratchett. Does he redefine the form? No – but he’s not trying to. Published during the 70s and 80s using the pseudonym Patrick Kearns, they conjure a strange, distant time when unions could have power, aristocrats could be penniless, eccentricity and science had room to breathe – and so did the short story.

It’s traditional to start anthologies with a bang and we do here with How It All Began… in which a curious caveman’s foundational inventions irritate his companions. We then enter a chaotic, more contemporary world with shades of Ealing comedy. Nature misbehaves, as does suburbia. Small town Blackbury and its bizarre residents are explored in various adventures. Long-form prose clearly suited Pratchett best, but this collection still delivers worthwhile gifts. Those who know his voice will see how quickly it was established and glimpse how fierce and large it would become. For newcomers, this is a fine Pratchett tasting menu.

Fiction

A kaleidoscopic family saga

Held

Anne Michaels

Held Anne Michaels

A kaleidoscopic family saga

Anne Michaels is still best known for her 1996 first novel, the multi-award-winning Fugitive Pieces. That title could serve as a description of this new book, a novel made up of scraps of storytelling and essayistic fragments. Science, hauntings and the way love complicates the linearity of time are themes that recur insistently in this episodic novel, which has been longlisted for the 2024 Booker prize. If opened out and rearranged as a sequential narrative, its story would be a four-generational, female-centred family saga. These lives could have been the stuff of a century-spanning, continent-spanning epic, but Michaels chops them up and rearranges them to make something odder and more formally interesting – a kaleidoscopic narrative in which memories, dreams and supernatural visitations are as integral to the patterning as real-world events. We are carried back and forth in time. Each section introduces new characters, different settings. Readers will pick up echoes. The lovelorn man called Aimo who is following the second Anna in Finland in 2025 (Michaels’s time slippages allow her access to the future as well as the past) must be the child whose musician parents we saw being expelled from Estonia for thought crimes in 1980. At one level these tenuous personal links hold together the disparate stories out of which the novel is constructed. At another – the level of thought and theme – the links are stronger. Held is full of lacunae – great gaps of time in which characters die or give birth or are exiled or despair. Like one of those elaborate knitting patterns, it is largely made up of holes and absences. Its stories are told in glimpses. It is for the reader to join the dots.

Crime fiction

Unlikely serial killers

Holly

Stephen King

Holly Stephen King

Unlikely serial killers

Holly opens with a scene of peculiar horror. In 2012 Jorge Castro, a teacher in a university town, is jogging on a misty evening. He sees two colleagues, professors Emily and Rodney Harris, struggling to load Rodney in his wheelchair into their van. He offers to help push the chair up the ramp. Too late, he realises their objective. Jorge wakes confined to a cage in their basement. Eleven years later, Holly Gibney has just finished participating in her mother’s funeral over Zoom when a new client, Penny Dahl, leaves a voice message begging her to investigate her missing daughter Bonnie. Slowly, Holly begins to connect the dots between Bonnie and other disappearances in the neighbourhood over the years. Stephen King’s resilient, solitary private detective has appeared in four recent novels. But this, as the title implies, is her book. As a character, she leaps off the page – dogged and resourceful, drawn to a profession that requires the sorts of interpersonal skills she struggles with because of her autism.

The novel is not so much a whodunit as a whydunit, moving between Holly in the present and each of the Harrises’ victims over the years. Each capture is evoked in devastating detail. Holly, as one would expect from a King novel, goes deep into the darkness. Lyrical and horrifying, Holly is a hymn to the grim pursuit of justice. The detective’s dogged search for truth drives the book; Covid-19, Black Lives Matter, Trump and the 6 January insurrection are all persistent themes. Even the Harrises are railing against the injustices of time and age. And the novel itself is striving towards an expulsion of poison, and a healing.

History

What haunts us

Fear

Robert Peckham

Fear Robert Peckham

What haunts us

Robert Peckham began writing this while he was a professor at the University of Hong Kong, as Beijing cracked down on freedom in the name of security. He resigned in 2021, appalled by the ruthless methods deployed to stifle opposition: “fear stalked a city that a few years before had buzzed with optimism.”

In this remarkable study, Peckham explores how fear has been used to both assert and challenge authority during the last 700 years: “fear becomes a lens for reconsidering what power is and how it works”. Importantly, he shows how revealing the history of this slippery concept and its relationship to power “may help us avoid being exploited by it in the future”. Among his conclusions are that fear is not always inimical to freedom, and that it can be used to bring about political change: “it is a mistake to assume that modern freedoms have been won by the abrogation of fear from political life”.

He begins in the 14th century, when plague devastated Europe and fear “unleashed a powerful destabilising force that affected every aspect of life”. In the 16th century, he shows how religious conflicts led to the demonisation of dissenters, provoking the persecution of Jews and Muslims, as well as witch scares: “fearmongering was a feature of the period”. During the industrial revolution fears coalesced around cities, the rise of the “volatile masses” and new machines. Indeed, it was a period torn between boosterism and pessimism about technology, as is our own age, with its varied responses to the “promises and perils” of nuclear power, AI, robotics and biotechnology.

Peckham’s brilliant survey of fear is both erudite and wide-ranging, drawing on the history of politics, religion, philosophy and technology to explore everything from our responses to God and war, financial markets and new viruses. It’s also a timely book, with anxieties about freedom of speech and the weaponisation of misinformation rarely out of the headlines: “we’re captives of the burgeoning clickbait industry, consumers in a metaverse that rejigs our psyches and modifies our behaviours. Fear always comes back to haunt us online”. In a modern world characterised by “illiberal democracy and authoritarian populism”, this important book offers much-needed insight, including a nuanced vision of fear that “sees grounds for hope, not despair, in uncertainty”.

Memoir

In retrospect

Father & Son

Jonathan Raban

Father & Son Jonathan Raban

In retrospect

In 2011, at the age of 68, critic and novelist Jonathan Raban “was transformed into an old man”. What felt vaguely like a hangover was diagnosed a few hours later as a stroke. With the right side of his body paralysed, Raban spent time in intensive care before being transferred to the neurological ward of the Swedish hospital in downtown Seattle (born in Norfolk, he moved to the US in 1990). He left in a wheelchair five weeks later and survived for more than a decade, dying in January this year. During that time he worked on a memoir.

It’s a brave book, not so much because of the physical difficulties he overcame in writing it, but because it takes him back to childhood and the challenges his absent father endured during the second world war.

Like most former servicemen, Peter didn’t talk much about his wartime experiences, dramatic though they were. But the letters he exchanged with his young wife Monica disclose some of what he went through, and to track his father’s wartime journey Raban supplements those letters with his extensive research. It’s a tale of cruelly separated newlyweds, and between the lines there’s a second love story as Raban celebrates his teenage daughter, Julia, whose promptness in getting him to hospital saved his life.

In a long career, Raban was best known as a travel writer. But he disliked the label and rightly felt that his books offered insights of a different kind; people and politics mattered more to him than places. Any book, he thought, should roam as freely as it likes and this final volume is an illustration of that.

Biography

A subversive voice

Daughter of the Dragon

Yunte Huang

Daughter of the Dragon Yunte Huang

A subversive voice

Born in Los Angeles in 1905, the actress Anna May Wong was the daughter of a laundryman who became a global celebrity. She appeared as an extra in her first film in 1919 and was later lauded as “The World’s Most Beautiful Chinese Girl”. In Germany, where she played the title role in the “smash hit” film Song (1928), she met Walter Benjamin who was clearly smitten, writing that “everything that is heart appears reflected in her eyes”. The following year she appeared in the British film Piccadilly, a portrayal of louche London now regarded as “a cinematic masterpiece”. Its plot reflects her own life story: a rags-to-riches fantasy that ends tragically. As the film roles dried up, Wong spent her final years in Los Angeles “with a drink in one hand and a cigarette in the other”, dying at just 56 in 1961.

Coming of age during the film industry’s meteoric rise, the fact that she managed to bridge the transition from silent to sound movies and then to television was, says American historian Yunte Huang, “a powerful testament to her talent and tenacity”. In her four-decade career she appeared in more than 60 films, a dozen stage plays, several TV series, and many vaudeville shows.

The final work in his trilogy on famous Chinese Americans, Huang writes powerfully of the prejudice Wong faced in her Hollywood career, at a time when Western actors usually played the lead and yellowface was common. In 1932, she starred alongside Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express. The sultry steeliness of Wong’s character was “the real engine driving the Shanghai Express”, but she earned a fraction of Dietrich’s fee.

Huang argues eloquently that Wong spoke “with a subversive voice” which challenged America’s “bigotry and injustice toward those who simply look different”. Illustrated throughout with wonderfully evocative photographs and combining cinema history with social commentary, his study offers a moving portrait of a screen siren who is “far more complicated than her legendary celluloid image would suggest”.

History

Nerds who loved words

The Dictionary People

Sarah Ogilvie

The Dictionary People Sarah Ogilvie

Nerds who loved words

The Tory xenophobes who police our coasts should watch their words. The so-called English language is actually a multicultural hubbub, jumbling together classical derivations. English is happily borderless, and the same is true of the Oxford English Dictionary which, as Sarah Ogilvie says, set out in the mid-19th century to trace words back to “their natural habitat”, wherever that may be.

Officially, the first headquarters of the OED was an iron shed in a north Oxford garden, but from the beginning this was a crowdsourced project. Ogilvie, tracking down leads from an address book kept by one of the earliest editors, has unearthed hundreds of anonymous volunteers on all five continents who collected recondite words or trawled unreadable books for illustrative quotations.

A few of Ogilvie’s dictionary people are lurid characters: she identifies three murderers, one cannibal and several institutionalised lunatics. Noting that “overeducation” was the official reason for confining one unfortunate woman in 1895, she wonders whether the OED can be held responsible for the diagnosis of madness; on reflection she admits that the habit of reading not for overall meaning but to pick out single words suits “quite a few of us who are neurodiverse, or who present on the autism spectrum”.

English, like the communities in which it circulates, remains a gloriously impure mess, and all the OED can do is impose alphabetical order. We hope in vain for a universal idiom that will pacify the world; what we have instead is the differently accented versions of English in which we speak, shout, argue and sometimes sing, using words that continue to proliferate, accumulate new meanings and tantalise would-be definers. We like to think that language is our creation; the truth is that it created us, and we are its babbling mouthpiece.

History

China’s underground historians

Sparks

Ian Johnson

Sparks Ian Johnson

China’s underground historians

Those looking for horrors in China’s recent past have no shortage of examples to choose from. For many, however, the struggle is being allowed to remember that such events happened at all. Memory is a compelling and slippery topic for students of China. Books such as Tania Branigan’s Red Memory have demonstrated how even people who lived through the Cultural Revolution struggle to make sense of what their memories are actually telling them. And the government demands total control over the official narrative: China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has warned against “historical nihilism”, believing the collapse of the Soviet Union came about because people were allowed to question, and lose faith in, the party’s version of the past.Pulitzer prize-winning journalist Ian Johnson tackles this difficult subject via China’s “counter-historians” who, through various mediums including documentary, fiction and even woodcuts, feel compelled to create a record of China as they see it. It is deeply satisfying to read a book about China that could only have been written after decades of serious engagement with the country.

This book takes its title from a magazine that had a short but heroic run in 1960, and is the subject of a film, available on YouTube, by renowned documentary maker Hu Jie. The magazine was published by a small group of students who had grown disillusioned with the failings of the Communist party. They were sentenced to decades in prison and, in the chaos of the Cultural Revolution a few years later, two were executed. As Hu tells Johnson, China’s previous historians “weren’t afraid to die. They died in secret, and we of succeeding generations don’t know what heroes they were … If we don’t know this, it is a tragedy.”

Memoir

A raw account of addiction and recovery

The Outrun

Amy Liptrot

The Outrun Amy Liptrot

A raw account of addiction and recovery

The Outrun is an uncompromising account of addiction and recovery played out against the blasted fields of Orkney. The book opens with a glossary and we are invited to enter Liptrot’s strange, raw world armed with a list of site-specific terms, clues to an unknown land. When we slide back in time to observe Liptrot’s mother, returning from the mainland with baby Amy in her arms, she pauses to greet her husband before he is escorted off the island in a straitjacket. Thus we meet two of the book’s central themes: things carried away or returned to Orkney, lives broken and restored by forces greater than themselves.

Right from the beginning the proximity of the edge is palpable, both in the sense of a tipping point or boundary. Liptrot began drinking at 15 and developed a habit so destructive she lost her London home, her lover and her job before she turned 30. The early chapters make for uncomfortable reading.

Liptrot writes without self-pity about “crying at parties to anyone who would listen about how my boyfriend had left me because of my drinking while swigging from a bottle of beer in one hand and a glass of wine in the other”. But even in this low state Liptrot affords flashes of awareness of a world beyond the bottle. She gets a job working for the RSPB and spends a summer searching for the rare and elusive corncrake. She moves further north, hopping from island to island, chasing extremes of sea and land where once she chased a drink. She is still seeking the next high, but she’s doing it with binoculars, a telescope, a snorkel.

Liptrot’s writing is strong and sure. Here is a writer finding her voice and The Outrun is a bright addition to the exploding genre of writing about place and our place in the natural world.

Fiction

A powerful reimagining of Maria Callas’s life

Diva

Daisy Goodwin

Diva Daisy Goodwin

A powerful reimagining of Maria Callas’s life

It’s more than 100 years since the birth of Greek-American soprano Maria Callas, and still no one in the opera world has rivalled her. Equally resilient is her reputation as a prima donna whose offstage dramas overshadowed her onstage triumphs.

Daisy Goodwin’s fourth novel reasserts Callas’s devotion to her craft, depicting a deeply serious artist whose life is lived in service to her prodigious gift. Until, that is, she meets Greek shipping billionaire Aristotle Onassis. Their turbulent love affair frames a narrative that begins when they first cross paths at a high society gathering in Venice in 1959, and ends shortly after Onassis betrays her by marrying Jacqueline Kennedy in 1968.

Flashbacks capture a series of exploitative relationships – with a gossip columnist friend, with her decades-older husband/manager, and with the controlling mother who never loved her. The novel’s pacing matches its heroine’s drive. It’s strong on dialogue and delights in descriptions of haute couture gowns and bedazzling jewellery. However, like Callas herself, it’s at its strongest on stage, conjuring the trance-like rigours and transcendent thrills of performances around the world, including her final operas.

Goodwin admits to having taken “dramatic licence” in her rendering of Callas’s life, and she’s sanitised it, too, omitting references to drug abuse and some of the most toxic aspects of her codependency with Onassis, unbreakable even after he humiliated her. Instead, Diva focuses on how heartache deepens Callas’s artistry and, once her singing career is over, shows a woman finally finding her own true (speaking) voice, and with it liberation and fresh opportunities. It’s fiction, of course, but who wouldn’t wish that ending for a talent so great she was known simply as La Divina?

Biography

How an artist was shaped by a city

Giacometti in Paris

Michael Peppiatt

Giacometti in Paris Michael Peppiatt

How an artist was shaped by a city

In the 1960s, the fledgling art historian Michael Peppiatt moved to Paris with a letter of introduction to Alberto Giacometti from Francis Bacon. He was still plucking up the nerve to deliver it when he learned that the Swiss sculptor and painter had died just days earlier. He has been preoccupied by Giacometti ever since, and his new book sets out to understand exactly how the artist’s distinctive talent was shaped by Paris during its artistic heyday. Personal and appealingly painterly, this is an immensely readable biography of the man and the city.

Source link